To be a girl in a sea of men. This is one of the themes in Netflix’ new series, The Queen’s Gambit. The show follows Beth Harmon (exquisitely played by actress Anya Taylor-Joy), a child who ends up parentless, and eventually gets mentored in chess by a janitor in the basement of an orphanage. The prodigy earns her way to the World Championship in order to work her way up to the best, a Russian named Borgov. All this is set against the backdrop of the Cold War, a fascinating parallel to explore between Capitalist and Communist nations meeting in peace to celebrate the art of Chess.

The fictional story is based off a 1983 book of the same name by an American writer named Walter Tevis. Was it based on anyone in particular? The official answer is no. The New York Times‘ chess expert surmised that she was probably inspired by Bobby Fischer, the US child prodigy who defeated a Russian grandmaster during the Cold War. In all the reviews I’ve read on the show and the book, not one person mentioned the Cuban female underdog, Maria Teresa Mora Iturralde. She was a woman who beat the majority of her male competitors during the Cuban National Championship in 1922, but was never allowed to compete with men globally during those years. There is no specific story of someone holding her down, but rather Maria Teresa is an emblem of a brilliant woman lost in the shuffle of a mans sport, lacking any career development, or international competitions that could have allowed her to reach her potential. To put it short, this is what people mean when they use the word “systemic” means of sexism. Perhaps, in a perfect world, Maria Teresa would have defeated Bobby Fischer *AND* the Russian champions of the world — had she been given the chance.

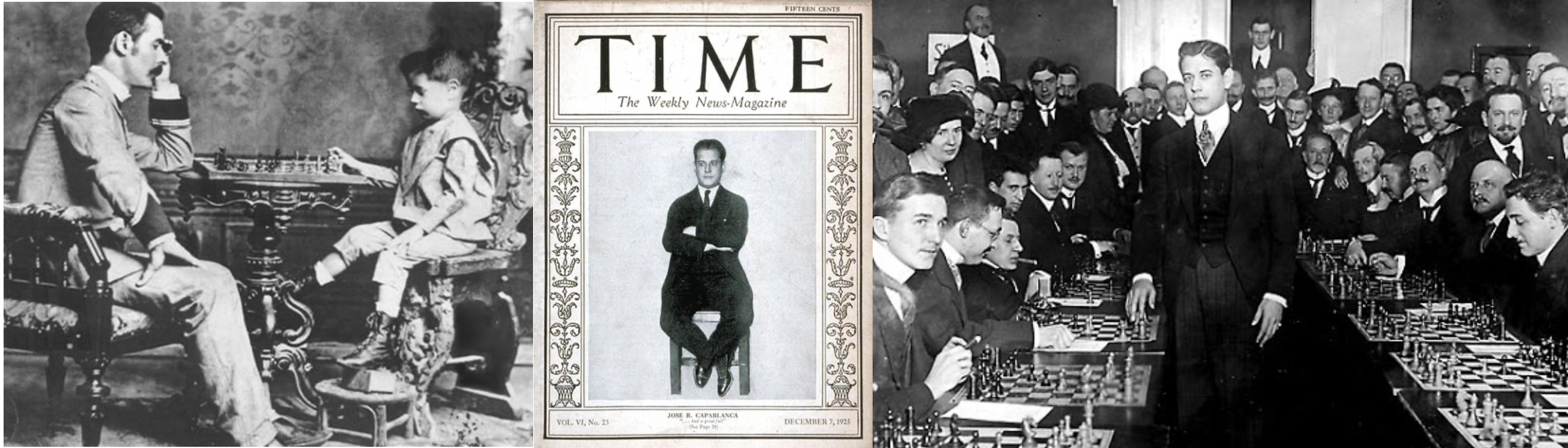

If this seems far fetched, consider the fact that she was also the only woman to have truly challenged José Raúl Capablanca (by some accounts, there is an unconfirmed rumour that she beat him in a 3 game session) . Who is Capablanca? He was considered one of the best Grandmasters in the world, and a founder of modern chess. Did we mention that Capablanca is also Cuban? If you think I am name-dropping too many obscure Cuban references, look no further than the Netflix show itself for the cinematic nods. As Beth Harmon enters high school, the loner strolls into the library to ask if they have any books on chess. The librarian offers her the first book that she should gobble up — by José Capablanca.

Before we get into the minutia of these players, allow me to position the context of Cuban chess within the world stage. Let’s use the show as another reference. In the final scene of Queen’s Gambit, Beth Harmon enters the Russian world championships hall to meet all of her opponents. She prepares to meet the penultimate player before her final face-off with Bergov, the World Champion. The intimidating Russian before him is described as “the world champion before Elizabeth Harmon was born”. He was noted as having “crushed Bronstein in Havana”, placing him in the upper echelons of Chess society. It is at this moment in the show, that one realizes that Russians and Cubans have a tremendous reverence for the game as study masters. The series even comments on how Russians unite together in gaming groups to help raise each others skills, something American players never did due to their “individualism”.

“The Soviets are murder” says the amateur twins in the series just to prepare Beth. “It’s like ballet, they pay people to play chess”. To an American, this is a foreign concept , but to Russians and Cubans, the game has been supported by the government for decades. It was important for the Cuban government to be respected in Chess as illustrated by their bid to host the World Chess Olympiad after the Revolution, offering ample spending and amenities for players attending, totalling 5 million dollar budget for that one event in 1966. This was the tournament that had Fidel Castro playing against Bobby Fisher for that infamous photo-op.

There was also the time that Cuba held the Guiness World Records for the biggest simultaneous chess match in history in 2002, with 11,320 players duking it out in front of the Jose Marti square. In fact, let’s zoom out to the 1800’s. Austrian-born William Steinitz, the very first World Chess Champion from 1886 to 1894, visited Cuba often, alongside many of the greats of his time. It was a time of great wealth on the island, but also a time for top notch respect for the game’s essence, rolling out the red carpet for international players, be it airfares, hotels, and perks. “Havana is the El Dorado of Chess,” writes Steintz in International Chess Magazine (1888), “there you find true amateurs, who really play for the love of the game and the promotion of our noble pastime, for the benefit of the whole Chess community and without regard for self-interest. They invite the strongest Chess masters, whom they remunerate liberally and treat with the most considerate and generous hospitality, without any other object than to develop the skill of the guest for the entertainment of Chess at large”. From mansions to public parks, the whole nation was a play zone.

Both in the Soviet Union and Cuba, the importance of Chess education is fostered since childhood. In Cuba, there is a Vedado-based organization named ISLA (Latin American Higher Institute of Chess) as well as national TV broadcasts of Chess classes. In a society that is freshly catching up with internet in the 21st century, Cuba is sadly creating less Grandmasters than it did in the past, which is altogether a world problem, given the speed and distraction of modern day technology.

But back to Maria Teresa. How has history forgotten her? To understand the importance of Maria Teresa competing with Capablanca, one first needs to understand the legend of Capablanca. In 1921, the World Chess Championship was held in Havana, and Capablanca won the title, thereby putting Cuba on the world map for the game. By four years old, Capablanca was beating his own father. By 12 years old, Capablanca became the champion of Cuba, and by 29 years old, he became champion of the world. He held the title of World Champion from 1921 to 1927. Capablanca died in 1942, and shortly after the 1959 Revolution, Fidel Castro kept the chess flames stoked by holding the first major tournament in 1962 at the Habana Libre hotel, and so continues the post-revolutionary fever until today as discussed earlier. Capablanca is buried at the Colón Cemetery and is respected worldwide as one of the beloved grandmasters of the game.

Just like Capablanca, Maria Teresa Mora grew up beating her own father at the game, and was entered into a youth tournament at 11 years old — which of course, she won. In 1917, American Chess Bulletin published an article entitled Havana Has Another Prodigy. The article claimed that she began playing at 8 years old. By the age of 14 years old, Maria Teresa was known as the only person to ever have studied under Capablanca. He never bestowed that honor to anyone else. She was special to him, and he nurtured the curious girl for just a moment.

In 1922, she exceeded all expectations. Maria Teresa became the only woman to ever to have competed with men in the Cuban championship and won (see the full Cuban Chess champions here). After that, the only World competitions she entered were women only — first in Buenos Aires 1939 (coming in 7th), and in Moscow 1950 (winning 4 and drawing 4). She entered the Cuban Women’s Chess Championship which she dominated as winner from 1938 to 1960, when she retired. In 1950, Maria Teresa was named the first Latin American woman to be given the Women’s International Master title. According to Cuban folklore (which is not yet verified, and we are in the process of investigating), the story goes that when Capablanca and Maria Teresa finally competed against each other, it was a three game series. She won twice and had a draw for the third game. Nobody could have imagined the pupil would beat the teacher. In typical early 1900’s fashion, she was remembered to have said “¡Ay qué pena, le he ganado!” (“oh how embarrassing, I’ve won”).

The Queens Gambit novel was written in 1983, without a particular player in mind, but presumably an amalgamation of several grandmasters studied by Tevis. Chess experts claim it’s loosely based off Bobby Fisher’s aggressive playing style. Of course in the 80’s, it would never be typical to describe a woman’s style as aggressive. There is a humorous moment in Queens Gambit when her adopted mother reads the Chess Review out loud, describing this new red-head girl player on the scene — “She’s out for blood” reads the article. Maria Teresa would have never been described with such fire back in 1920’s. It wasn’t until 2005 that a woman actually competed in the World Chess Championship. Judit Polgar put up a great fight but didn’t make the final prize. With 14% female representation in the US Chess Federation, it is clear that women have to surmount the sexism that still comes with the game.

In an embarrassing interview, Bobby Fisher fueled the fire by saying that women are “terrible chess players”. When asked the reason, he responded “I don’t know why, I guess they’re not so smart. They have never turned out a good woman chess player. Never one, that could stand up against a man in the history of chess”. Then, like a contradicting child, he adds “I’ve never played a women in a tournament game”.

For every Bobby Fischer that was discovered, trained, exalted, encouraged, and surrounded by peers — there was probably one Maria Teresa Mora (1922 Cuba victory) left behind… or a Lisa Lane (1959 US Womens Champion), or a Judit Polgar (2005 competitor in World Championship). The difference is that these women were probably never nurtured to their fullest. Never coached, without a role model. They were simply freaks of nature, smarter than everyone around them, and somehow found themselves in the room, with 64 squares on a board to challenge their mathematical brains. In my minds eye, I’d like to think Beth Harmon was less of a Fischer inspiration, and more of a Maria Teresa reaching her potential.

Beth’s young chutzpah also comes from the spirit of Paul Morphy, another grandmaster that she obsessively studies in the series. Just like all the women in real life, Morphy never realized his full potential since he retired at the age of 22, and was found dead in his bathtub at 47 year old. Bobby Fischer looked up to Capablanca and Morphy the most. Fischer once said that Morphy had the talent to beat any player of any era.

Another fun fact: Morphy loved Cuba. In October of 1862, he passed by Havana (from New Orleans) on his way to Paris to play a few rounds with the strongest Habaneros in the game. On his way back from Paris, Morphy stopped again by Havana to play more games at a private residence — both of these visits are filled with wonderful stories and characters, all documented in “La Odisea de Paul Morphy en la Habana” (The Odyssey of Paul Morphy in Havana).

Morphy was another American, who played with strong intuition, and was known to defend himself well. Moreover, he could be called deadly in his approach (similar to Harmon’s “out for blood”). I suppose you can project whatever qualities onto Harmon’s character from any past chess giants, however, I will hold on to my own illusion, that Maria Teresa lives inside this character, and that Netflix finally allowed her to win the World Championship she deserved.

Mentored for a tiny moment in her life, Maria Teresa’s rough diamond shined just enough for a genius to take note. One of the most beautiful cerebral exchanges I found between a man and a woman comes from Capablanca’s book, My Chess Career, of which he writes about the lessons he gave Maria Teresa Mora as a child:

“There was in Havana a young girl of from 12 to 14 years of age who interested me a great deal. Not only was she intelligent and modest in every respect but, what is more to the point, she played chess quite well (I believe that today she probably is the strongest lady player in the world, though only 15 or 17 years old). I offered to give her a few lessons before I sailed. My offer was accepted, and I decided to teach her something of the openings and the middle-game along general principles and in accordance with certain theories which I had had in my mind for some time but which I had never expounded to anybody. In order to explain and teach my theories I had to study, so it came about that, for the first time in my life, I devoted some time to the working of the openings. I had the great satisfaction of finding that my ideas were, as far as I could see, quite correct. Thus it happened that I actually learned more myself than my pupil, though I hope that my young lady friend benefited by the dozen or so lessons that I gave her. It came about that I thus strengthened the weakest part of my game, the openings, and that I also was able to prove to my own satisfaction the great value of certain theories which I had evolved in my own mind.” (source: Tartajubow)

It takes a real man to admit that a 14 year old girl upped his game. Still, I find it curious why Capablanca did not mention Maria Teresa Mora’s name in the book, just listing her as “a young girl”. Perhaps even the greatest and confident men can shake in their boots in the presence of a smart woman.

DISCLAIMER: Nov 16, 2020 – It has come to my attention that the fact Maria Teresa beat Capablanca is disputed in history. The victory over Capablanca has been written in 3 historical Cuban blogs, however, none of these blogs are considered definitive media that can be fact-checked from. Due to this reason, I have adjusted the article to claim that her win over Capablanca falls under urban legend. This matter has launched me into a new search for facts, seeking out Cuban historians who can confirm or deny this story. The rest of the article which details the prodigy’s great and unrealized potential to compete with men on the world stage is 100% true. Stay tuned to this blog for developing reports on this final fact to be determined. I intend to get to the bottom of this, for Teresa’s sake, as well as the greater good of Chess history.

Leave a comment